Prospect Theory: Mental Accounting… Delayed Production

This post is another on the topic of behavioral economic theory, after writing about understanding bias in decision making by the manager and General Manager and further by looking at how Prospect Theory can explain why teams are hesitant to trade prospects, this post will look at mental accounting. Despite the name of the article, this post doesn’t relate to Prospect Theory, it’s just a perfect tagline for anything prospect related on this website because of the relation to economics and baseball.

Mental accounting is relatively easy to explain as it is a commonly applied principle in the house. Say you have $100 of disposable income (using small numbers for ease of illustration) and half of that goes to electric, utilities, mortgage, etc. leaving you with $50 in discretionary income. While making your budget, you decide that you can spend $20 on clothes, $20 on books, and $10 on movies. If a shirt costs $7, a book $6, and a movie costs $3, after buying two shirts, two books, and three movies, you are left with $15 that you are free to spend. An “econ” (those considered to think rationally and optimally, but in practice don’t exist) would think that they have $15 to maximize their remaining utility (utility here means happiness). This is just standard economic theory:

max U(clothes, books, movies)

wrt clothes, books, movies

st to $7(clothes) + $6(books) + $3(movies) <= 15U(clothes, books, movies) is some utility function with the budget constraint being prices*optimal quantity <= Income. Solve the problem, and you get the optimal quantity of each item the consumer will buy to maximize their utility. But what behavioral economics says is people mentally account. They have used $14 of their $20 allotted to clothing, so they can no longer buy a shirt for $7, $12 of $20 for books has been used, so they can buy one book for $6, and all but $1 of their allotment for movies has been spent, meaning this consumer can no longer buy a movie. The economist would not think of this as rational, as the consumer is not maximizing their utility, but it is a common budgetary practice. You cannot spend what you do not have in your budget, even though there is money allocated elsewhere that can be spent. Thaler (1999), sums up the research on why mental accounting matters when it comes to understanding decision making.

Additionally, Thaler and Johnson (1990) look at gambling with “house money”, or the money that you win from gambling (you didn’t have that money before you walked in, so it’s less risky to gamble with it even if you are risk averse). Despite Prospect Theory predicting people will be risk seeking when in losses, Thaler and Johnson found that prior losses are not fully integrated with future outcomes, ultimately leading to potentially more risk aversion if the following gamble does not create a break-even point. Here, you’re anchoring to the initial wealth. The authors also find that when breaking even is possible, integration fully occurs and when faced with a loss, risk seeking occurs.

Fully, in conclusion, Thaler and Johnson write “It seems plausible that the failure to integrate losses observed in our experiments would be even stronger across attributes. That is, a loss in one domain will increase the loss aversion felt with respect to other domains. If this is true, then in negotiations it will be particularly difficult to obtain concessions from a side that has already agreed to accept a loss.” In baseball, some General Managers are considered harder to trade with than others. Jerry DiPoto loves to swing moves while others are considered more risk averse. The Pirates were always rumored with the big names at the trade deadline: Jon Lester in 2014 and David Price in 2014 before settling for no trades. The Red Sox in 2014, coming off a World Series, ended 71-91. In this instance, the Pirates were already facing a loss in trying to trade for the soon to be free agent. Trading for a player with two months of control hardly moves the needle for postseason odds in a given year, but players do matter, and it helps the clubhouse.

Dallas Keuchel at the 2017 trade deadline was disappointed that then Astros General Manager Jeff Luhnow didn’t bring in a player or two to help the club try to win the World Series. The Astros went on to trade for Justin Verlander, who pitched to a 1.06 ERA for Houston in September and a 2.21 ERA in the postseason. The trade happened at the last minute, but the Astros brought in a reinforcement, one who is a future Hall of Famer. While the Astros had the cheating scandal on their way to the World Series, they still went and got the player that their number one starter (Keuchel 2.90 ERA in 2017 and 3.15 over previous four years) wanted. While the numbers might not show it, it does help send a signal.

Going back to the Pirates attempted trade for Lester, Huntington seemed, from an outside perspective, to already be risk averse. Even after applying a discount to the future wins, in all likelihood, the Pirates would be trading away more wins than they were receiving. This coincides with Thaler and Johnson stating that “in negotiations it will be particularly difficult to obtain concessions from a side that has already agreed to accept a loss.” Huntington, already facing a loss, wouldn’t be willing to give up more prospect capital (delayed production in this case) for Lester.

***

That was all a long winded discussion of mental accounting and loss aversion, explaining how mental accounting works and its relation to loss aversion. This is the paper, and concept, that I really want to focus on: Invest now, drink later, spend never: On the mental accounting of delayed consumption (Shafir and Thaler, 2006). For the focus of this post and the relation the article has to baseball, delayed consumption will be delayed production of prospects.

Thaler and Shafir (will drop Shafir from here out) write about how purchasing and consumption over time, the value of things can change, citing depreciation and appreciation, market value, etc. In baseball, this would be like a form of a prospect that is either drafted or signed off the international market. Gregory Polanco, for instance, signed for $150,000 in 2009 out of the Dominican Republic and graduated as Baseball America’s number 10 prospect in baseball. Since signing, Polanco’s prospect status, and thus trade value, appreciated and he was a valuable player to have in the system. However, Mickey Moniak was the first overall selection in the 2016 MLB Draft and ranked 17th by Baseball America entering the 2017 season. Entering 2020, Moniak ranked as the Phillies ninth best prospect by Baseball America, writing “He most likely ends up as a backup outfielder who can play all three spots.” This is a prospect status who has depreciated and is less valuable in the trade market. Gregory Polanco (who will be used later as an example), was valuable to the Pittsburgh Pirates in 2013 and 2014 as a guy who could be used to acquire a big player or as a future cornerstone for the team. That didn’t occur, but at the time of his prospect status, he was a player for the future. On the flip side, while Moniak did end up making the Major Leagues, he was the first overall pick and you want more than a backup or low-end starting outfielder.

Thaler looks at wine consumption – how do you value a bottle of wine that you bought for $20, that sells for $75 a bottle now, and your then decision (give to friend, drink), how is this bottle of wine valued? But this is the question that really sticks out: “Suppose you buy a case of Bordeaux futures at $400 a case. The wine will retail at about $500 a case when it is shipped. You do not intend to start drinking this wine for a decade. At the time that you acquire this wine which statement more accurately captures your feelings? Indicate your response by circling a number on each of the scales provided.”

In this instance, the bottle of wine appreciates but it is delayed consumption. This is similar to a prospect – the prospect’s trade value either appreciates or depreciates and the consumption (the production that the player provides, either in trade value or production for the Major League club) is delayed. The results in Thaler’s paper show that “I feel like I made a $400 investment, which I will gradually consume after a period of years” was the statistically significant endorsement from the survey. Again, similar to how a prospect will gradually produce for a number of years for a club. Thaler calls this, “Invest now, drink later, spend never!”

In the first study (wine consumption), the authors find that 55 percent of participants find that they lose $75 (the value of the bottle despite buying for $20) if the bottle is broken, this $75 represents what is called the “replacement cost”, or how much would it cost to replace this bottle? This is an interesting finding because Thaler found that drinking or giving away the bottle had no costs because the bottle was paid for long ago had the plurality of the votes in the first study.

These results are replicated in study three, where college students are asked about purchasing a ticket in their sophomore year and will be on campus for two more years. They have the option of purchasing a series of tickets for $120 for eight concerts (four each year) giving a price per concert of $15, or for buying individual concert tickets for $25. The most popular endorsement was “I feel like I made a $120 investment, which I will gradually consumer over the course of the next two years.” To follow up with the study, seven concerts have occurred, leaving one in the final year where the price of ticket goes for $50. The most common answers are that the ticket costs $15 (price paid given the series option), free (spent money a long time ago), and a saving of $35 (difference between market price and price paid).

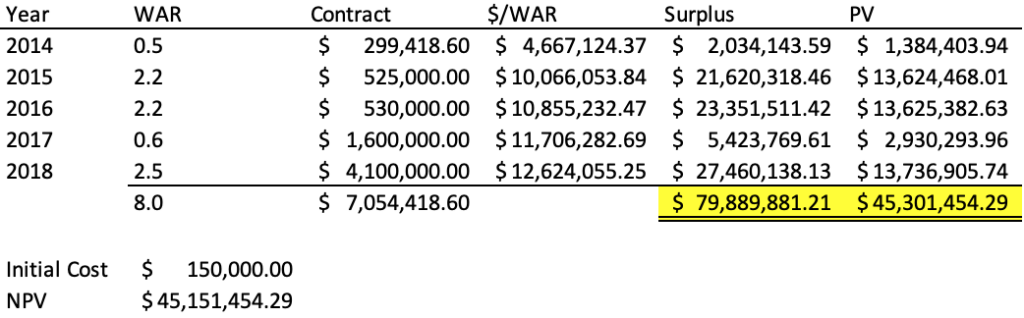

After losing the ticket, the most common answer is that the student lost $50, or the value of the ticket on the open market. At purchase, the ticket is an investment and at the time of attending the concert, there was no cost but if the ticket was lost, then the cost is the full replacement cost ($50). Reusing Gregory Polanco as our example, we know he signed for $150,000 in 2009 and was called up in 2014. That season, Matt Swartz found that dollar/WAR to be an estimated $6.4 million, and with a growth rate of 6.1 percent from 2000-2009, we can calculate the dollar per war estimate through 2018 and calculate Polanco’s surplus to the Pirates (Using about a half year of service for 2014). Given the length of a high schooler to MLB in the draft is five years, Polanco’s timeline of being signed in 2009 and debuting in 2014 follows a similar path. This allows us to use 2009 as the base year in a present value calculation for Polanco.

From 2014-2018 (his rookie year where he played 89 games and his first four full seasons), Polanco provided an estimated $80 million in surplus. He only averaged about two wins a season over this time, making him a 50 with the potential to be a 55 (if you’re using the Theo school, that’s a B2 with a low B1 type ceiling). That’s a valuable player to have, especially on a team friendly contract that is relatively low risk, but just not what was the expected median outcome. How Polanco fits into this mental accounting framework is that his initial $150,000 is the investment. The delayed production is what he provides the Pirates in terms of production at the Major League level. While Polanco didn’t live up to prospect ranking, the Pirates acquired $40.151 million in present value. It could’ve been more if he lived up to the hype, but he’s saved the Pirates $45.301 million since 2009 in the free agent market. And the cost is so far in the past, that it is essentially $0 being recognized in this mental accounting concept; it’s “free” production.

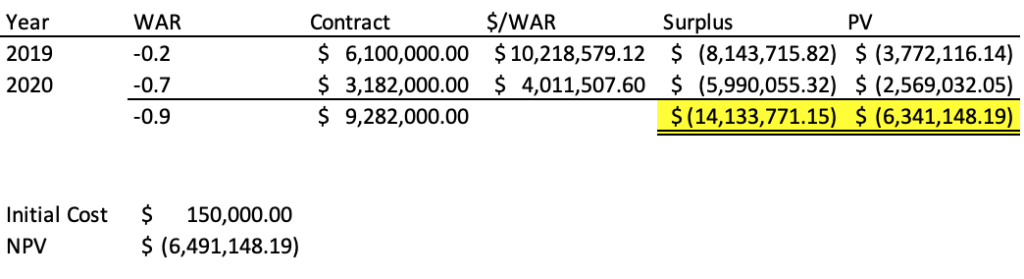

However, over the last two years, after a shoulder injury at the end of 2018, Polanco has provided the following surplus (2020 is a dollar per win of $10.9 million given the $6.4 million estimate in 2009 and 6.10 percent growth rate) but given the season is 37 percent that of normal, we’ll use $4.01 million and his contract of $8.6 million will be $3.182 million). His value is now negative, similar to how the bottle of wine was broken or how a student lost the ticket.

In these two years, Polanco has provided the Pirates with a negative $6.5 million return, leading to questions if the club will bring him back at $11.6 million – he also has a $12.5 million team option ($3 million buyout) for 2022 and a $13.5 million team option ($1 million buyout) for 2023. Given that Polanco has cost the Pirates $13 million (i.e. losing the $75 bottle of wine or $50 ticket), and MLB contracts are guaranteed, keeping the right fielder is now a resuscitated cost (the initial investment and the contract cost are now active again). Polanco’s production is not what it was expected, and we now remember the costs associated with him as a loss. Instead of spending that money on Polanco, it could have been spent elsewhere, the Pirates are out the investment.

***

Different forms of bias, Prospect Theory, and mental accounting are all ways that the traditional economic models fall short. By understanding these concepts, and applying them to the game of baseball, we can better understand managerial and roster decisions. The end goal is to always maximize win probability and total wins (thus playoff probability), but there are errors in decisions stemming from traditional models. Recognizing, understanding, and avoiding them can help in achieving sustained success.

This post has been updated to reflect the error in calculation for value from 2014-2018

0 Comments on “Prospect Theory: Mental Accounting… Delayed Production”